When your language becomes a crime: the Kurdish teacher tortured in Turkish prisons

Northern Aleppo countryside – Dijla Khalil – North-Press Agency

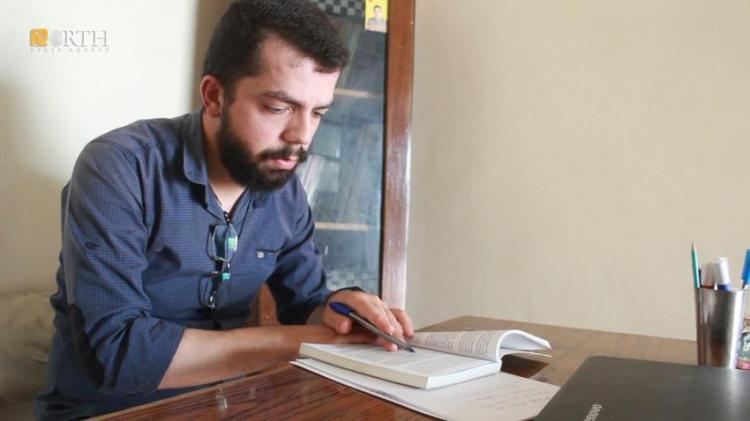

Whenever 27-year-old Jamil Khoja, who comes from the village of Kakhera in Mu'batali district in the Afrin region, carries a book to read or papers to prepare a lesson, he remembers what he saw what he and his father were subjected to two years ago by Turkish-backed armed opposition groups. If he tries to forget what he has gone through, he will remember the marks of torture on his body, but despite all that he continues on, though his capabilities have been affected.

He says: "Two years after I was arrested, I am still suffering from the effects of torture. The ligaments in my knees are torn, I cannot see well, and my psychological and health condition in general has deteriorated. I suffer from frequent pain in the stomach and head, and wherever I blink I remember what I was exposed to."

Determination after all

After his arrival to the northern countryside of Aleppo, where the rest of his family lived, he went back to teaching his mother tongue, Kurdish, in addition to giving educational lectures and seminars to teachers, writing articles, reflections, and poems. "I will collect all my literary productions in a book. I have written and composed three songs that some artists from the culture center in the northern countryside of Aleppo will record soon.”

At the beginning of the imposition of the total curfew, underwent surgery to implant a lens in one of his eyes, and after his slight improvement, he created an educational group on WhatsApp and Facebook to teach Kurdish grammar.

Khoja notes that about 200 people joined his group. "I teach Kurdish grammar, the basics of teaching the Kurdish language and lectures on the history of Kurdish literature, where I try to communicate information via audio recordings."

They burnt my office

Khoja’s story began in March 2018 when Turkish forces and their armed opposition groups took control over his village. On that day he was forced to burn his library, which contained more than 200 books, for fear that it would fall into the hands of the Turkish-backed armed opposition groups. "It was a very difficult moment for me, as if you were wiping out your history of life."

But the burning of his library, that included books on Kurdish literature, philosophy, and history, did not protect him from arrest and the most severe forms of torture, the effects of which he still suffers. "They called through the loudspeaker in the village mosque that day, and asked the people to gather in the village square. They did not exclude men, women, or the elderly, threatening those who did not come to the square."

The Turkish-backed Sultan Suleiman Shah al-Amshaat arrested him along with his brother, father, and a number of young men from his village without charge. “They took us to Qarmatlaq village in the Sheikh Hadid suburb. I cannot forget what happened. They used all methods to torture us: hitting, kicking, slapping and insults. There weren’t any clear charges against us.”

After two days of torture, the group released his brother and father, who became paralyzed as a result of torture and severe beatings. "My father suffered about thirty blows to the head, causing him paralysis."

The Human Rights Organization in Afrin documented, in a report published on January 16th, 54 individuals from Afrin who were tortured to death killed by members of the Turkish army and its affiliated armed opposition groups.

An excuse to torture

A week after his release, Turkish forces arrested Khoja a second time. "They arrested me again at seven in the evening and asked me about my work. I answered them that I was a teacher, and during the interrogation, they beat me on my head with a thick plastic hose. "This time they told me that my charge was that I was teaching for the party, referring to the former Autonomous Administration in Afrin.

"The Turkish army officers used my profession in education as an excuse to torture me. They took us to a Turkish headquarters, where they photographed us. We were handcuffed and blindfolded."

As a result of the torture, his eyes were damaged, as he was suffering from poor vision. "They put us inside a carriage, and my glasses fell. One of them crushed my glasses with his foot and elbowed me in the eyes. Then I lost consciousness and woke up blindfolded in a car. There were four people above me, piled on top of each other. They beat our faces ruthlessly.”

He was then transferred with a number of other young people into Turkish territory, where they stayed for two days. "The beating continued through the morning and evening. We stayed without food. When I asked for water they poured it over my face. When I asked them to loosen my handcuffs they tightened them more. My hands were tied behind my back. Whenever I tried to move them I felt that my veins would be cut.”

He considers the torture by Turkish forces "much worse than that of the armed group, as the torture was systematic, psychological and physical.”

In August 2018, Amnesty International indicated in a report that Turkish forces had Syrian armed groups commit serious human rights violations against civilians in the city of Afrin, including arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, confiscation of property, and looting.

"They asked us to utter the two testimonies," (declarations of the oneness of God in Islam) Khoja added. "When we said the two testimonies, they shouted, ‘Allah u Akbar,’ as if we were infidels and just converted to Islam.”

After leaving prison, he was threatened by the Amashat group and then arrested a third time, and he forced to pay them $2,000 as a bribe.

Hope to return

Khoja then decided to leave his village and go to the northern countryside of Aleppo, where the displaced people of his area live. “My father and I paid one of the Turkish-backed armed groups 100,000 Syrian pounds to take us to the city of Azaz, and from Azaz we headed to Manbij. There I felt that I was born again. I have tasted so much torment by the armed groups and the Turkish army."

Once in Manbij, his father was admitted to a hospital for treatment. They stayed there for several months until his father recovered. “While my eyes’ condition worsened and I could not see anything, I used glasses with special lenses for severe myopia.”

Khoja is working as a teacher again and continues his creative writing, hoping that one day he will be able to go back to Afrin and to his village, which he misses greatly. “Liberating Afrin and all our lands from the Turkish occupation is my wish,” he said.