QAMISHLI, Syria (North Press) – When coronavirus was sweeping the world in June, northeast Syria was almost free of the virus.

However, the region recorded its first three cases of the virus in mid-June, one of which died and two of which recovered. This region, with very weak medical capabilities, has stood alone in the fight against the pandemic since July.

How did coronavirus manage to spread in the region? How did the local authorities deal with situation in light of the fragile health system, limited capabilities, and lack of international assistance?

Pandemic outbreak and lockdown

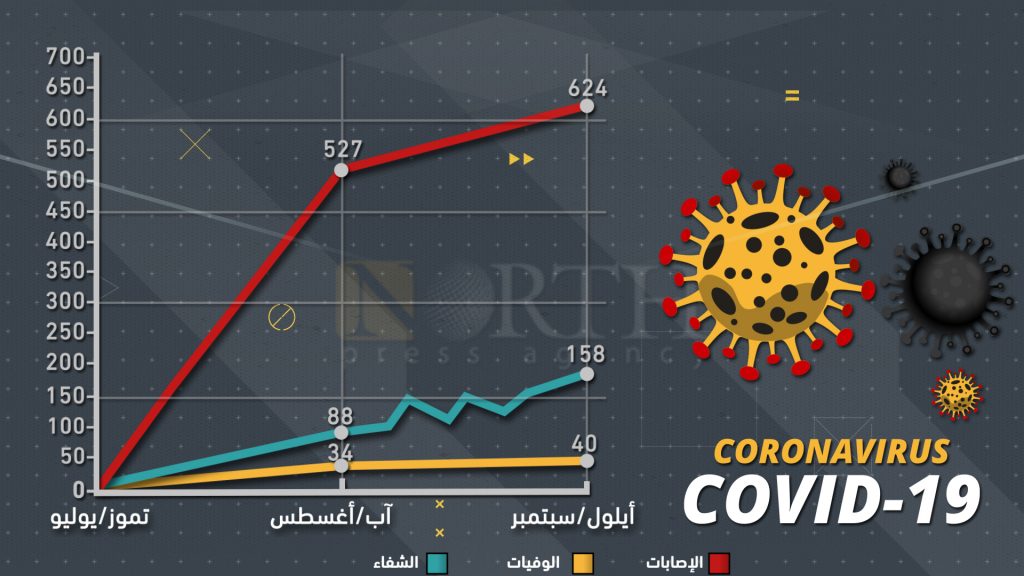

After three consecutive months of protective measures imposed by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), cases of coronavirus infections in the region have multiplied rapidly.

The first phase of the lockdown started on March 23 and ended on June 16. This was the period in which three cases of the virus, one of whom died and two of whom recovered, were recorded.

After the lifting of the lockdown a month later and the recording of new cases, local authorities announced the second phase of the lockdown, from July 13 to August 27.

The decision to lift the lockdown came after AANES officials’ certainty about the futility of the lockdown in light of the pandemic’s spread and the hundreds of infections in the region.

Medical teams have been unable to provide exact numbers of infections, as many remained at home without contacting authorities, according to the Autonomous Administration Health Board. “The figures that are announced depend on PCR tests only. However, there are a lot of people who are infected and in contact without realizing that they are infected. This is the reason of the wide spread of the pandemic,” the Health Board said.

Qamishli airport: ground zero

The primary reason for the spread of coronavirus in the region is the entry of thousands of people into Qamishli city from Damascus, the hotspot for the virus in Syria, every week.

“Investigations proved that the virus came into the region from the Qamishli Airport,” said Jiwan Mustafa, co-chair of the Autonomous Administration Health Board.

On July 11, an airplane with 400 people aboard took off from Damascus and landed at Qamishli airport.

“All the 400 people were not tested, neither in the airport nor in the medical points,” said passenger Jiyan Antarat.

During the first phase of the lockdown, Autonomous Administration medical teams were testing the arrivals, but due to the emergence of smuggling and lack of cooperation from the Syrian government, the medical teams stopped testing, as they felt it useless, according to the Health Board.

A Health Board medical team to test arrivals from Qamishli airport – North Press

No cooperation with Syrian government

Mustafa said that the administration lifted the lockdown because “the officials in the airports of Damascus and Qamishli did not cooperate with the Autonomous Administration.”

“The distribution of spheres of influence between the Autonomous Administration and the Syrian government, and the latter’s lack of cooperation on the issue of preventative measures, led us to believe that the spread of the virus is inevitable. The measures we took were beyond our capabilities,” Mustafa said.

“Hundreds of people enter Qamishli every day without passing through our medical points, so the lockdown was meaningless. In addition, the economic situation that stormed the region as a result of the collapse of the value of the Syrian pound and the wave of high prices pushed us to lift the lockdown,” he added.

Qamishli Airport receives six cargo flights every week, in addition to two flights by Syrian Airlines and two other flights by the private Cham Wings company, meaning that an average of 3,500 people arrive to northeastern Syria on a weekly basis.

Mustafa accuses airport officials of smuggling travelers, keeping them in homes in the vicinity of the airport to be smuggled out the next day. Government forces do not allow the Autonomous Administration to enter the airport to test the arrivals, and officials working in the Qamishli airport did not respond to North Press’s requests for comment.

High costs

In the instance of a suspected coronavirus case, Kurdish Red Crescent emergency teams follow a mechanism to keep the infected person at home until the symptoms of infection are no longer present.

However, Anas Mahmoud, one of the first people infected with the virus, said that the medical teams did not rush to respond to the first cases.

Farhan Suleiman, director of the emergency team in the Jazira region, said that they follow up the patient’s situation over the phone until the infection is confirmed.

“We warn the patient to stay at home, and we give him some advice to follow until we take a sample from him,” he added.

There are only 17 quarantine centers in the regions of northeastern Syria, with each center containing 25-60 beds designated for moderate and critical cases, in addition to the existence of only about 55 ventilators in the entire region.

According to the Health Board, the equipment is not sufficient, so they are constantly trying to import the necessary needs “in preparation for the winter…We expect the infections to be increased in winter.”

The government’s National Hospital in Qamishli contains 19 beds and 4 ventilators, according to an official in the hospital’s quarantine department.

“Since the first phase of the lockdown, we have spent about 3 billion Syrian pounds (over 1.4 million dollars at the time of this report) on medical supplies. More than 1,000 people have been PCR tested so far. Each PCR test costs $70,” Mustafa said.

The Autonomous Administration is working to treat the infected for free, and all medical expenses will be free due to the poor living conditions of the residents of northeastern Syria, as Mustafa said.

Lockdown in name only

When the number of the infections increased from 8 to 57 in a week, the Autonomous Administration imposed a complete lockdown in the Jazira region on August 6.

Despite the Autonomous Administration’s measures that prevented gatherings, photos of meetings, parties, and cultural activities were published during the same period, showing a lack of commitment to the measures.

Despite the imposition of the lockdown, the number of the infections reached 397 on June 25.

Mustafa stated that the measures are not as strict as the previous lockdown, as they became useless in the face of the already-spreading virus.

Mustafa noted that they moved from the phase of preventing the virus from entering the region to the phase of dealing and coexisting with it.

Coexistence strategy

After the rapid spread of the virus, the Autonomous Administration decided to adopt the “coexistence strategy.” For this, it lifted the lockdown and imposed new and more effective measures that would reduce the number of the infections.

The “strategy” depends on the population’s awareness of dealing with the virus and methods of prevention.

On August 18, the Autonomous Administration imposed a fine of SYP 1,000 (about 50 cents at the time of this report) on anyone not wearing a mask in public.

The end of the lockdown was accompanied by a set of measures during which the Autonomous Administration prevented gatherings such as wakes, weddings, and collective prayers in mosques and churches.

Economic pandemic

The lockdown measures imposed heavy economic burdens on the population, as a large percentage of them are day laborers depending on a daily wage.

Qamishli taxi driver Abu Shero said that during the lockdown, he had to work in secret to secure his daily sustenance.

“It is true that there was a lockdown, but we had to coexist with it and secure our daily sustenance,” he said.

Residents face many difficulties in committing to the preventative measures in light of the economic conditions in Syria, especially after the sanctions under the US Caesar Act, which contributed to the worsening of the living situation.

Khorshid Alika, an economic researcher living in Germany, believes that the tense economic situation has a strong negative effect on the virus’s rapid spread.

Alika pointed out that the residents’ lack of commitment to quarantine is related to economic obligations, and that coexistence with the virus is necessary in the face of economic hardship.

Alone in the confrontation

Jiwan Mustafa said that they are in contact with several authorities regarding mechanisms to combat the virus, the most prominent of which are the health institutions in the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq (KRG). “We have almost daily contact with the laboratories of the Kurdistan region,” Mustafa said.

During the past months, the KRG sent six testing devices to the Health Board, in addition to various medical supplies.

“Neither the Global Coalition nor the Russians have provided any support to efforts to combat the spread of the virus in our regions,” Mustafa said.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reportedly provided occasional support to the health sector in the Autonomous Administration, but the support came mainly through the Syrian government, which has been accused of manipulating and interfering with aid provided to the region.

“The support provided by WHO was not sufficient to confront the virus,” Mustafa said.

The WHO previously tweeted that it sent a medical cargo weighing 30 tons by road to Qamishli “to meet the emergency health needs of the most vulnerable people in the region,” without specifying who would receive the aid.

“We did not receive any aid from WHO, nor did we report receiving support,” the Autonomous Administration Health Board said.